Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a critical medical condition in which severe liver dysfunction leads to kidney failure. It occurs primarily in individuals with advanced liver cirrhosis or acute liver failure. The impaired liver function disrupts blood flow and triggers changes in the body’s regulatory mechanisms, causing kidneys to malfunction. HRS is characterized by rapidly deteriorating kidney function, resulting in fluid retention, electrolyte imbalances, and ultimately, organ failure.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is the Main Cause of Hepatorenal Syndrome?

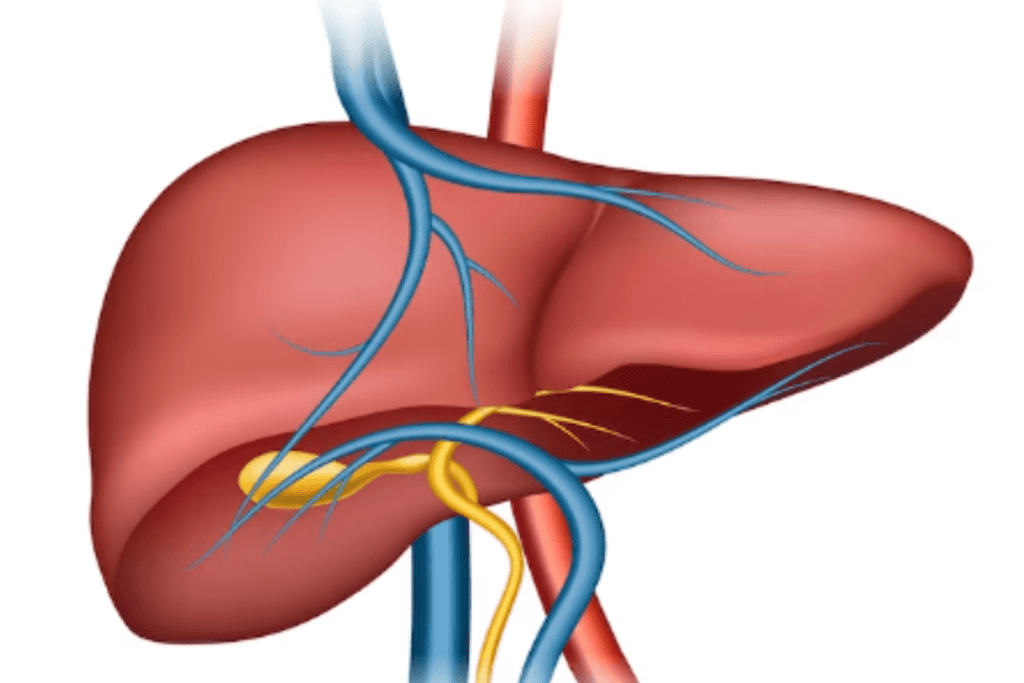

The main cause of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is advanced liver disease, particularly cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a condition where the liver becomes severely damaged and scarred due to chronic injury, often caused by long-term alcohol abuse, viral hepatitis infections (such as hepatitis B or C), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune diseases, or other factors. As cirrhosis progresses, it can lead to portal hypertension, which is increased pressure in the blood vessels that carry blood from the digestive organs through the liver.

This increased pressure can disrupt blood flow to the kidneys, leading to kidney dysfunction. The exact mechanisms that lead to HRS are complex and involve a combination of reduced blood flow to the kidneys, activation of vasoconstrictive pathways, and alterations in various hormones and signaling molecules. Overall, the underlying liver dysfunction and circulatory changes are the main contributors to the development of hepatorenal syndrome.

What are the Symptoms of Hepatorenal Syndrome?

The symptoms of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) can vary in severity and may be similar to those of other conditions. However, there are key clinical features that can help distinguish HRS from other forms of kidney dysfunction.

Common symptoms and characteristics of HRS include:

Reduced Urine Output

One of the hallmark features of HRS is a significant decrease in urine production. This is often accompanied by oliguria (low urine output) or anuria (absence of urine production), which indicates severe kidney dysfunction.

Fluid Retention

HRS can lead to fluid accumulation in the body, resulting in symptoms such as swelling in the legs (peripheral edema), abdominal distention (ascites), and fluid buildup in the lungs (pulmonary edema), causing difficulty in breathing.

Electrolyte Imbalances

The kidneys play a crucial role in regulating electrolyte levels in the body. In HRS, electrolyte imbalances can occur, leading to disturbances in levels of sodium, potassium, and other ions. These imbalances can contribute to various symptoms, including muscle cramps, weakness, and irregular heart rhythms.

Hypotension

Low blood pressure is common in individuals with HRS due to the circulatory changes and vasoconstriction that occur as a result of kidney dysfunction.

Confusion and Altered Mental Status

The accumulation of waste products and toxins that the kidneys would normally filter out can lead to a condition called hepatic encephalopathy. This can cause confusion, altered mental status, and even coma.

Fatigue and Weakness

Individuals with HRS often experience fatigue and weakness due to the body’s inability to properly regulate fluid and electrolyte balance, leading to overall physiological imbalances.

Jaundice

In cases of advanced liver disease, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) may also be present due to the liver’s impaired ability to process bilirubin, a waste product.

How is Hepatorenal Syndrome Diagnosed?

Diagnosing hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) involves a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and exclusion of other possible causes of kidney dysfunction. The diagnostic process is typically carried out by a healthcare professional, often a hepatologist or nephrologist.

Here’s an overview of the steps and tests involved in diagnosing HRS:

Clinical Assessment

The healthcare provider will review the patient’s medical history, including any known liver disease or cirrhosis, as well as any recent changes in kidney function or symptoms.

Physical Examination

The provider will perform a physical exam to assess for signs of fluid retention (edema), jaundice, abdominal distention (ascites), and altered mental status, among other potential indicators of HRS.

Laboratory Tests

Blood tests are crucial for evaluating kidney function, liver function, and potential electrolyte imbalances.

Key laboratory tests include:

Serum Creatinine:

Elevated levels of creatinine suggest a decline in kidney function.

Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN):

Elevated BUN levels can also reflect kidney dysfunction.

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR):

Calculated from creatinine levels, it provides an estimate of kidney function.

Liver Function Tests:

Including bilirubin levels, which can indicate liver dysfunction.

Electrolyte Levels:

To assess for imbalances like sodium and potassium.

Urine Tests:

Analysis of urine may reveal abnormalities related to kidney function, such as proteinuria (presence of protein in urine) and changes in urinary sediment.

Imaging

In some cases, imaging studies like abdominal ultrasound or Doppler ultrasound may be performed to assess the blood flow to the kidneys and evaluate the presence of ascites or other complications of liver disease.

Exclusion of Other Causes

Diagnosing HRS also involves excluding other potential causes of kidney dysfunction, such as acute kidney injury (AKI) due to infections, medications, or other factors.

Response to Treatment

One important diagnostic criterion for HRS is the patient’s response to specific treatments, particularly the administration of medications that improve blood flow to the kidneys (vasoconstrictor agents) and intravenous albumin. If kidney function improves after these interventions, it can support the diagnosis of HRS.

What are the Two Types of Hepatorenal Syndrome?

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is classified into two types: Type 1 and Type 2. These classifications are based on the severity of kidney dysfunction, the rapidity of onset, and the response to treatment.

Here’s a brief overview of both types:

Hepatorenal Syndrome Type 1 (HRS-1)

Severity:

HRS-1 is the more severe form of HRS. It represents a critical and rapidly progressing condition.

Onset:

HRS-1 typically develops over a very short period, often within days. This rapid onset distinguishes it as an acute and urgent medical issue.

Kidney Dysfunction:

In HRS-1, there is a severe and abrupt decline in kidney function. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which measures how well the kidneys filter waste from the blood, drops dramatically. This results in significant fluid retention and waste buildup in the body.

Response to Treatment:

HRS-1 is notoriously challenging to treat. It doesn’t respond well to medical interventions, and the prognosis is poor. Mortality rates are high, often occurring within a matter of weeks if the condition is not effectively managed.

Characteristics:

HRS-1 is characterized by a sharp increase in serum creatinine, a waste product that indicates impaired kidney function. Additionally, urine output decreases markedly, leading to oliguria (low urine output) or anuria (absence of urine output). Severe kidney dysfunction is often associated with more advanced complications of liver disease, such as severe ascites (abdominal fluid accumulation) and hepatic encephalopathy (altered mental status due to liver dysfunction).

Hepatorenal Syndrome Type 2 (HRS-2)

Severity:

HRS-2 is considered less severe compared to HRS-1, though it is still a serious condition requiring medical attention.

Onset:

HRS-2 develops more gradually over a period of weeks to months. This slower onset differentiates it from the more acute HRS-1.

Kidney Dysfunction:

In HRS-2, kidney dysfunction is not as rapidly progressive as in HRS-1. The decline in GFR is typically less severe, and the overall impairment of kidney function is milder.

Response to Treatment:

HRS-2 is more responsive to medical treatment compared to HRS-1. With proper management of underlying liver disease and supportive care, kidney function might stabilize and improve to some extent.

Characteristics:

HRS-2 is often associated with less advanced liver disease compared to HRS-1. It might develop in individuals with compensated cirrhosis or less severe liver dysfunction. It’s important to note that while HRS-2 has a better prognosis than HRS-1, it still requires careful monitoring and treatment to prevent further deterioration.

What is the Treatment for Hepatorenal Syndrome?

The treatment for hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) involves a combination of approaches to address the underlying liver disease, improve kidney function, and manage complications. The specific treatment strategy can vary based on the type of HRS (Type 1 or Type 2), the severity of the condition, and the individual patient’s overall health.

Here are some key aspects of HRS treatment:

Treating Underlying Liver Disease

Liver Supportive Measures:

Addressing complications of cirrhosis, such as controlling bleeding from varices, managing ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdomen), and addressing hepatic encephalopathy (altered mental status), can help stabilize the overall condition and indirectly benefit kidney function.

Liver Transplantation:

For individuals with advanced cirrhosis and HRS, liver transplantation is the ultimate treatment option. A successful transplant provides a healthy liver that can restore normal liver function, potentially leading to improved kidney function.

Addressing Kidney Dysfunction

Vasoconstrictor Agents:

Medications like terlipressin or norepinephrine can help constrict blood vessels, raising blood pressure and improving blood flow to the kidneys. By counteracting the vasodilation that occurs in HRS, these medications aim to enhance renal perfusion.

Albumin Infusion:

Intravenous albumin administration helps expand the blood volume, enhancing circulation and promoting better kidney function. Albumin’s colloid osmotic pressure helps prevent fluid leakage from blood vessels.

Other Supportive Measures

Avoiding Nephrotoxic Drugs:

Certain medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and some antibiotics, can harm kidney function. These drugs should be avoided or used with caution in individuals with HRS.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance:

Close monitoring of fluid intake, diuretics, and electrolyte levels is essential to maintain proper balance. Fluid restriction may be necessary to avoid worsening fluid accumulation.

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS):

TIPS is a procedure that involves creating a shunt (a channel) within the liver to redirect blood flow from the portal vein to the hepatic vein, thus reducing portal hypertension. By doing so, it can alleviate pressure on the kidneys and improve overall circulation.

Supportive Care:

Close monitoring in a hospital setting is common for individuals with HRS. Monitoring includes assessing fluid balance, electrolyte levels, kidney function, and overall clinical status. Management of complications like fluid retention and altered mental status is crucial for patient stability.

Remember that the treatment approach for HRS is highly individualized and requires the expertise of healthcare professionals specializing in hepatology and nephrology. It’s essential to tailor the treatment plan to the patient’s specific circumstances, including the type of HRS, the underlying liver condition, and the overall health of the patient. Early intervention and a collaborative approach among medical specialists can lead to improved outcomes for individuals with HRS.

Conclusion

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a critical condition arising from advanced liver disease. It’s classified into Types 1 and 2 based on severity and responsiveness to treatment. HRS-1 is acute and severe, often unresponsive to therapy, with high mortality. HRS-2 progresses more gradually, responding better to interventions. Addressing underlying liver disease, vasoconstrictors, albumin infusion, and supportive care are key strategies. Liver transplantation can be curative for some. Timely diagnosis, collaborative multidisciplinary care, and prompt treatment are crucial for improving outcomes and quality of life for those affected by HRS.

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1904420/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430856/

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/grp/2015/207012/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37258014/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8457138/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8330394/